2016 MSOTY: GAMES

/Games are what we're really here for, and these ones cinched the year for me. LET ME SHOW YOU WHAT I GOT.

Read MoreGames are what we're really here for, and these ones cinched the year for me. LET ME SHOW YOU WHAT I GOT.

Read MoreAre you a Terrible Timmy? A Jumping Johnny? A Spastic Spike? Or, possibly, a Veritable VORTHOS??

Read MoreHOW FAR is a new column, exploring developments in design between Then and Now.

Outdated... but relevant!

When I look closely at Old Thief and New Hitman, it’s hard to say that game design, at its core, has grown significantly deeper over the years. In terms of mechanics the games are nearly identical. Hitman and its cousins have merely grown in breadth, with larger, more lifelike spaces, binders full of scripted interactions, and overabundant audiovisual fidelity; but in terms of how they actually play, nothing has changed. By many names, it seems like we’ve been playing the same games all our lives.

Here: let’s compare about 15 minutes of gameplay from each title.

OLD THIEF - BAFFORD’S MANOR

I’ve done a bit of sewer crawling, but haven’t yet been able to breach Bafford’s Manor. I meander in overlapping paths, not having any strong idea of my position relative to the goal without the aid of a whirling minimap, but my headmap is filling in and I’m started to case the location. I find my way to a small, square shed out back of the Manor with a single guard. He steps away to patrol and I slip up behind him and konk his head. I move to the building, but the door is locked. When I turn around to explore, I see the bright, shiny key at the guard’s belt. I take it, open the door, and break into the Manor.

This is a very typical problem in video-games by now: defeat the enemy to acquire the key to unlock the door behind him. But it’s no less an elegant interaction for its commonness, for it can be flubbed. If we already have the key when we arrive, or if we kill the guard before we know he’s guarding a door, there’s no drama. Seeing the location, solving the problem/fighting the enemy, being barred access, and then realizing you had already earned it, is basic, but good, design. Looking at the map, I found I could have learned about the locked door earlier, stretching this first mini-plot arc even further. Of the few words written, arrows pointed at one area (the map is a true map - no dynamic pinpoints) and signaled “Well leads to basement -- One Guard!”

NEW HITMAN - SAPIENZA

I start out in a safehouse with some remote detonation charges. I could creep into the mansion through a window across a rooftop which I can reach from my third-floor safehouse, but there’s a huge chunk of map to the right I’m curious about. I drop down and explore the beach. There’s a clown, whose performance I interrupt, to the annoyance of the audience, by standing on his carpet. I toss a coin into his hat as apology and some guy yells at me not to throw things. Continuing along the whitesand beach I find a sewer entrance. I case the sewers, knocking out a worker and taking his Sewer Key and Red Plumber disguise - no Mushrooms though. I follow the sewers through a ruined tomb and surface beneath the steeple of a church. I ascend to the top, grabbing a crowbar along the way, and make a mental note for a future run that I can cut the cable suspending the churchbell. I make my way down to the cemetery, lay in a coffin just for laughs, then double back across the beach to the targets’ mansion again. Time to focus on the mission.

I was actually getting really into my bussing career til I remembered I was here to murder people.

Now, take note of the 18 years separating the two -- which story makes more sense?

I don’t mean to belittle Hitman. I love the game, its rotating arcade of custom challenges, its clockwork of looping level events, the tense yet articulate sequences of killing and sneaking. Hitman makes for great stories and unprecedented possibilities, just like Thief does. But for having come so much later in the history of game design, the game pushes few boundaries, beyond its Whoopie Cushion-meets-Gallows Humour emotional tone. All the graphical polish and dynamic sound and plausible-looking crowds of people and dozens of scripted, achievement-linked interactables in each level are just padding around what is, mechanically, the 1998 game Thief in third person. As another player wisely observed, Instinct mode isn’t there as a gameplay tool or character element; it’s a counterbalance against the game’s own obsession with graphical fidelity, to the detriment of visual clarity. Unlike the way animated figures blatantly pop out from the watercolour backgrounds in old Disney movies, Hitman’s high-fidelity housekeys and pipewrenches blur into their surroundings, obscuring their usability. Interactable objects may be indistinguishable from decorative textures without the highlighter-yellow silhouettes. Though Thief takes no pains to distinguish these tools through its UI, it really isn’t necessary, as these objects by their nature are interactable. Chests are for opening, levers are for pulling, fine china is for pocketing. That the opening and closing of all doors in a room strikes this player as impressive speaks volumes about the queer point we’ve reached in current game design. Hitman’s spaces are so sprawling yet full of walls, that level design itself is insufficient to inform the player of where the patrolling enemies are; minimaps and X-ray heat-vision is simply compensation for this unfortunate drawback of massive, sprawling in-and-outdoor levels in a stealth game.

Even the freshly retooled disguise system is just an extrapolation of the visual stealth mechanic in Thief. Disguises operate like small areas of personal shadow, obscuring you from detection except to a dangerous few, who can “illuminate” you through your disguise if they see you, depending on the disguise. Switching from disguise to disguise to gain access to new areas is not significantly more interesting than using the water arrows in Thief to create patches of shadow to creep through the level.

Oh, I guess Hitman has cover "mechanics.” That’s new. I don’t think I’ve been in a situation where wall-hugging would have hidden me any better than just standing as near to that wall as possible. It’s a strange and unnecessary conceit, an artefact of shooter design left in just because.

Though it looks like shit - charmingly so - or maybe because it looks like shit - Thief’s affordances, mechanics, and exposition are communicated deeply and clearly at every level of the game’s design. To a designer with about half the computational power that we play with today, the idea of devoting a team to illustrating an animated, inaccessible background at full clarity would be absolutely ridiculous. All they could afford to take seriously would have been the core design - the interactive component, the game - and that shows in how well it coheres, even today, with its dated graphics and interface. As much fun as I’ve had turning over every leaf in Hitman’s sprawling level designs, the challenge lists and purely scripted interactions ring out as more of an embellished tradition in the 1998 stealth genre than an evolution of it.

Can’t we go further??

As I was playing through 2014’s Wolfenstein: The New Order a little while ago it occurred to me that I was playing a great movie. After a few fervent early missions killing robotic mega-Nazis, you enter a peaceful homebase area and interact with a small cast of friendly characters. As I spoke to each of the rough-and-tumble renegades, scoured their candlelit quarters for juicy backstory details, and trawled through countless newspaper articles describing the establishment of the totalitarian Nazi superpower across the globe through the 40s and 50s, I realized I was part of a story that desperately wanted to be told in full. Much like a movie, it felt as if Wolfenstein wanted me to see each minute detail of its story piece by piece until everything came together in my mind. The key thing here is that the game wanted me to SEE these details -- and not PLAY them…

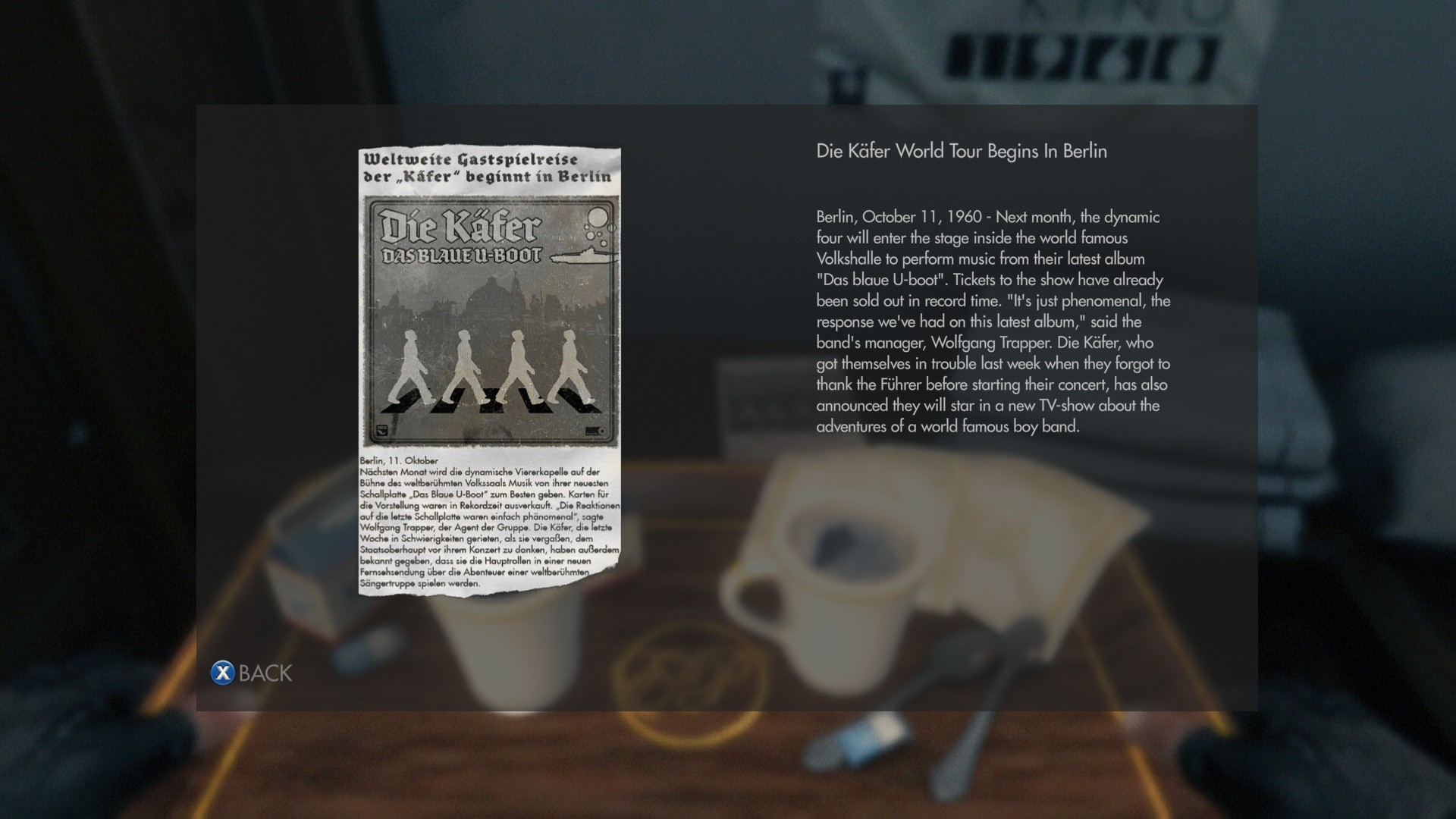

Click here for Nazi-approved, German-language Beatl- *aherm* Die Kafer smash-hit, "Mond, Mond, Ja, Ja".

Don’t get me wrong. I really enjoyed New Order overall, and I’d recommend it. But as a game it’s just mediocre. Strip away all these rich story details, tense dialogue exchanges (which you don’t control; you just sort of watch your character talk), and lovable characters, and you’ve got a fairly inarticulate dual-wielding run-and-gun corridor FPS game. If the writing had been weaker, I don’t think I would have been motivated to grind through some of the more tedious “DO THIS THING HERE!” challenges that the game inelegantly chucks you into. But it carries so well as a movie you want to know the ending to, that the anemic gameplay passes as fun a lot of the time. And this identifies a blurring line between games and film as the former continues to balloon as an industry -- what other entertainment medium has grown so large, so quickly?

In the wake of the financial success of consoles in the 90s, the largest budgets for videogame production are rising to compete with Hollywood films, with the star talent, CGI, and marketing campaigns to match. A co-worker of mine told me he’s interested in gaming: he moonlights as a foley guy for TV and commercials, and he suspects that videogames are where the real money is nowadays -- even for an industry as film-niche as sound production.

However I think this is a mistake. I think the real similarity between movies and gaming pretty much ends at budgetary magnitude. To treat gaming as just… home video in a different type of VCR sells it short of its potential, and leads to exploitative licensing cash-ins like the new Star Wars videogame. I do appreciate that some games work well as kind of surrogate films (looking to aforementioned Wolfenstein and Metal Gear Solid) but these linear narratives really feel like they sprawl too wide and deep to be contained in the silver screen; they take advantage of the affordances of gaming to tell a bigger story. And in the rare cases where the depth of gameplay matches the depth of story, nothing’s more fun. These days, many AAA titles aim to awkwardly recreate the cinematic experience through a controller and the result is usually a deadened game and a dull movie. I played through Hitman: Absolution and Deus Ex: Human Revolution when I built my PC last year, and both games seem to sacrifice so much of their well-loved gamey-ness for a dull, mass-appeal movie-ness. No player sits down and hopes not to push any buttons in a 10 minute interval. The difference in appeal between literary depth, and interactive depth, should be respected.

I mean, even in name they indicate something radically different. The whole activity of film isn’t called “movie-ing.” It’s too passive. As a medium, it’s called film or cinema - a simple noun. As a whole activity, the other medium is referred to as gaming - a present-tense verb; something that is being done. There’s plenty of room for flexing the semantics of this distinction but regardless it can be agreed upon that gaming needs to take a different industrial arc than film does, so those massive pools of resources can fuel innovation and interactivity, and not just mass-appeal spectacles.

Powered by Squarespace.